The National Museum of Scotland holds a very dear place in my heart, since I spent the majority of my MLitt dissertation working feverishly on the bead collections here.

My first visit to the museum was actually for a class. We were to wander around the majority of Scottish History and Archaeology, though our primary focus was the early medieval to Norse periods.

There are so many beads in this exhibit that I need to split up this post in order to talk about them all, and I’m only going to talk about the beads from the Romans to Norse for now. For anyone who loves beads, the Scotland galleries at the NMS are basically heaven.

There are so many beads in this exhibit that I need to split up this post in order to talk about them all, and I’m only going to talk about the beads from the Romans to Norse for now. For anyone who loves beads, the Scotland galleries at the NMS are basically heaven.

Let’s start today with the Roman beads. If you wander round the hall enough, you’ll notice a statue of a horse in one of the cases. Around the neck of this horse is a string of beads, most of which are faience melon beads. Throughout Scotland, these are the only beads I found that were pretty spectacularly associated with the Romans and basically no one else.

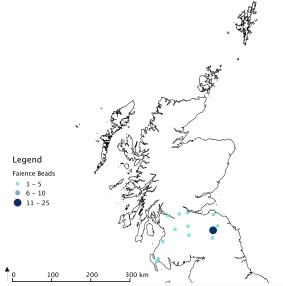

Faience, at least at the time of the Romans, was vitreous frit – a sort of precursor to glass. It was usually turquoise in colour, and the beads were nearly always melon beads (also known as gadrooned beads). When I mapped out all the faience melon beads I had documented from Scotland, they fell beautifully between the Antonine Wall and Hadrian’s Wall – the main area of Roman influence in Scotland.

Faience, at least at the time of the Romans, was vitreous frit – a sort of precursor to glass. It was usually turquoise in colour, and the beads were nearly always melon beads (also known as gadrooned beads). When I mapped out all the faience melon beads I had documented from Scotland, they fell beautifully between the Antonine Wall and Hadrian’s Wall – the main area of Roman influence in Scotland.

Another set of Roman beads you can find is in the same hall, just a different case (apologies in advance for the lack of focus in the photo). These are cobalt blue, turquoise, or green glass beads from Traprain Law. Some of these are segmented beads – beads that look like two or more separate beads that have been glued together. Segmented beads, like eye beads or melon beads, are a fairly widespread, fairly common bead type.

Others of these seem similar to beads I saw from Indian contexts, though I admittedly don’t know if there is a proper name for this type. The beads tend to be square or rectangular. The edge of one perforation is as you would expect for a square/rectangular bead. On the other, there are between two and four grooves, as if these areas had been worn away by a string. Fourth and fifth from the left and also fourth from the right are examples of these

There are also some wound beads in this photo as well as one bead that seems folded (the cobalt blue one that’s second from the right. The far one on the left is a silver foil segmented bead, made by sandwiching a layer of silver leaf between two layers of glass.

Most of the Roman beads I’ve seen are these turquoise faience beads or turquoise, cobalt blue, or bright green glass beads. I’ve also seen cobalt blue melon beads, which seem to mimic the faience beads. The display at the NMS has some really nice examples, so I highly recommend taking a look when you get the chance. There are TONS more beads – we’ll talk about early medieval stuff next week!

To get to the National Museum of Scotland from Edinburgh Waverly Station, exit the station and make a left. At the intersection, make a right onto Market Street. After roughly a block, you will see a green patch on the left side of the street with stairs leading up and away. Follow those stairs until you reach another road. This is St. Giles’s Street. Make a right, then take a left onto the next street (Bank Street). (Instead of following the stairs, you can also just follow Market Street until it reaches North Bank Street. Make a left onto North Bank Street, then a right onto Bank Street) Bank Street becomes George IV Bridge. Continue until you find Chambers Street turning off to the left. You’ll see a tower-like structure on the corner – this is the NMS.